The history of hearing aids is surprisingly long and fascinating. The sleek wireless devices we use today are the result of centuries of experimentation and innovation. While some people still imagine bulky plastic models, the reality is that today’s hearing aids are smaller, lighter, and far more advanced than ever before.

Let’s take a look at where they originated – you might be surprised to see how far things have come along!

History of Early Devices

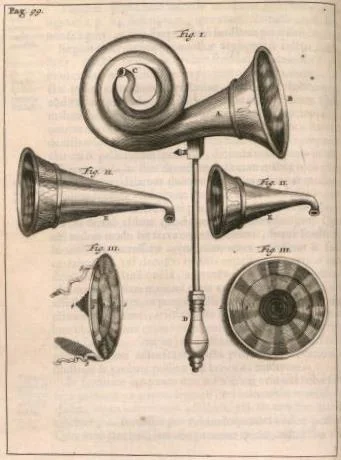

People have used tools to assist their hearing for centuries. As early as the 13th century, they used hollowed-out animal horns to help amplify sound.In 1588, Giovanni Battista Porta described wooden devices in Magia Naturalis that mimicked the ears of animals known for acute hearing.

In the 17th century, Sir Samuel Moreland introduced a large speaking trumpet made of glass. It was quite cumbersome, measuring around 2 feet 8 inches (81 centimetres).

Until the late 18th century, ear trumpets were made specifically for individual clients. Notable examples include the Townsend Trumpet, crafted by deaf teacher John Townshend, the Reynolds Trumpet made for painter Joshua Reynolds, and the Daubeney Trumpet. In 1800, Frederick C. Rein began commercially producing collapsible ear trumpets in London.

Rein also introduced hearing fans and speaking tubes—portable devices that helped amplify sounds. However, many people still found them bulky and impractical. It wasn’t until the introduction of smaller, handheld trumpets that these aids became more widely accepted.

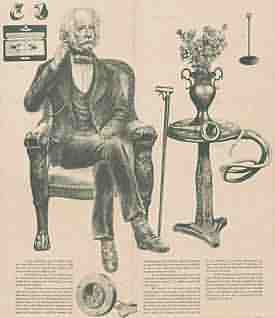

History of Hearing Aids - F.C. Rein & Sons

Rein became a pioneer in hearing technology creating history of hearing aids. In 1819, he was commissioned to create a specialised acoustic throne for King João VI of Portugal.

The throne featured lion-shaped openings on each armrest that acted as receivers. Sound entered through these mouths, travelled through an internal acoustic system, and was transmitted to the king’s ear via a speaking tube.

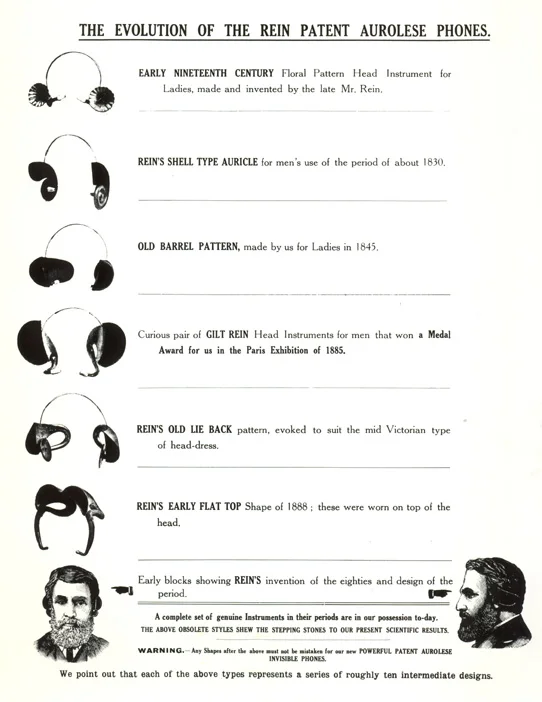

Rein’s ‘acoustic headband’ was one of the closest non-electronic forerunners to modern hearing aids. It featured a strap around the head to conceal the device. He also designed the ‘Aurolese Phones’, another headband-style hearing aid.

These came in various shapes, including a version with a spiral shell-like structure.

During this period, hearing aids were often hidden in clothing, furniture, or accessories to discreetly support individuals with hearing loss. Rein’s discreet and effective designs became widely popular. They remained in use until the telephone and microphone emerged in the 1870s and 1880s.

Advances of the 19th century and the First Electronic Hearing Aids

Rein wasn’t the only innovator of the Victorian era. In 1812, Jean Marie Gaspard Itard developed the first bone conduction device, inspired by Jorrison’s accidental discovery in 1757.

The first curved behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid found success in 1836. Soon after, patents were filed: Alphonsus William Webster in Britain (1836) and Edward G. Hyde in the US (1855).

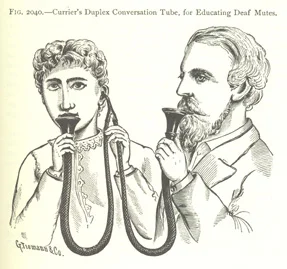

In 1874, Dr Constantin Paul created the binaurical cornet—a binaural conversation tube joined by a headband with a Y-shaped connection between the earpieces.

Toward the end of the 19th century, innovations came quickly. In 1879, Richard Rhodes invented the Rhodes Audiophone, followed by Enoch Henry Currier’s Duplex Earpiece in 1885.

These breakthroughs laid the foundation for the first electronic hearing aids, which emerged shortly after the telephone and microphone became widely used.

Inventors like Alexander Graham Bell, Charles Grafton Page, Innocenzo Manzetti, Antonio Meucci, Johann Phillip Reis, and Cyrille Duquet all played vital roles in developing early electronic hearing aids.

Telephones changed everything. Their ability to control loudness, frequency, and distortion revolutionized how people thought about hearing aids. In 1898, Miller Reese Hutchinson invested the first electric hearing aid, called Akouphone.

This early model used a carbon transmitter, making it portable. It took in a weak signal and, using electric current, amplified it into a stronger one.

History from Early 20th Century Strides Forward

In the early 1900s, Charles W. Harper launched his version of the carbon-type hearing aid, called the Oriphone. Siemens joined the industry in 1910 and, by 1913, produced their first electronically amplified hearing aid. Although bulky and hard to carry, these early models paved the way for future designs.

Then, in 1912, the Globe Ear-Phone Company introduced the first volume control for hearing aids. However, World War I soon halted progress, leading to a lull in invention during and after the conflict. Two years after World War I, Earl Hanson—a naval engineer—created the first vacuum-tube hearing aid.

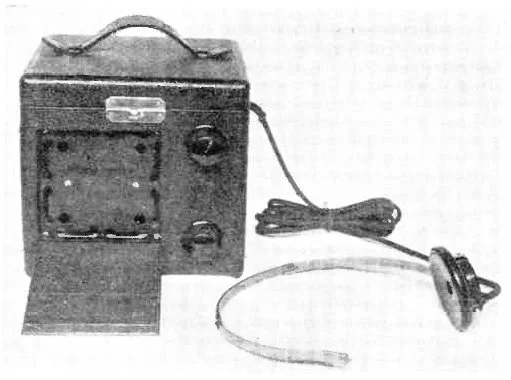

The Vactuphone used a telephone transmitter to convert speech into electrical signals. These signals were then amplified and sent through the receiver. Learning from Siemens’ early setbacks, Hanson’s design was portable—it weighed just over 3 kilograms (7 lbs).

The interwar years proved fruitful for hearing aid users. Vacuum technology finally gave people with hearing loss a device that resembled a modern hearing aid. In 1926, custom earmoulds received their first US patent, laying the foundation for the system still used today.

In 1932, Sonotone Corporation introduced the first wearable bone conduction hearing aid.

Four years later, the ‘Master Hearing Aid’ (MHA) was developed to assist in hearing aid fittings. The notion of miniaturisation, of making things smaller and more compact, then began to make great strides forward.

By 1938, vacuum tubes had been successfully miniaturised. Telex then released a small wearable vacuum tube hearing aid.

History of Hearing Aids - The Aftermath of WWII

When the Second World War began, hearing aid development slowed significantly. However, the technological progress made by wartime militaries later influenced advancements in audio assistive devices. One example is automatic gain control, which improved significantly alongside radar technology. In 1948, Multitone of London patented the first hearing aid with this feature and released a wearable version.

Another breakthrough came from Samuel Ruben, who developed the balanced mercury cell. It was widely used in munitions, walkie-talkies, and metal detectors during the war.

After the war, this battery system was adopted for hearing aids and other compact electronics.

History of Hearing Aids - The Advent of the Transistor

Although first proposed in 1907, the transistor only became practical thanks to the efforts of John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley. Their invention dramatically changed how hearing aids operated.

Although first proposed in 1907, the transistor only became practical thanks to the efforts of John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley. Their invention dramatically changed how hearing aids operated.

At Bell Labs in New Jersey, the trio discovered a method to boost signals using gold contacts and germanium crystals. In 1956, they received the Nobel Prize in Physics—a well-deserved honour given the transistor’s global impact. Today, transistors power nearly all modern electronics. Many consider them one of the greatest inventions of the 20th century.

In hearing aids, transistors quickly replaced vacuum tubes. They were smaller, more energy-efficient, and caused less distortion.

This breakthrough accelerated miniaturisation. Hearing aids could now be worn entirely in or behind the ear—or even integrated into spectacles.

Throughout the 1950s, various versions of hearing aids were tested. In 1958, Jack Kilby created the first integrated circuit, marking the beginning of the shift from analogue to digital technology.

Digital Hearing Aids and the Latter 20th Century

The digital revolution for hearing aids began in the 1960s, led by Bell Telephone Laboratories’ early experiments with speech and audio signal processing.

These experiments used large, slow digital computers—too bulky to be portable—but they laid the groundwork for future sound recording and transmission.

In the 1970s, Garett AiResearch, Texas Instruments, and Intel developed the first microprocessor. This breakthrough allowed computers—once large and unwieldy—to become much more compact.

Edgar Villchur also played a key role. He developed an analogue multi-channel amplitude compression device that split audio signals into frequency bands. As a result, louder sounds were amplified slightly, while quieter sounds received greater amplification—allowing for more natural listening.

The next advancement came with hybrid devices. These combined analogue components—amplifiers, filters, and signal limiters—with a programmable digital section. Their low power use and compact size made them highly effective for the time.

Companies like Etymotic Design, Mangold and Lane, and Graupe & Co successfully developed and refined these early semi-digital models.

In the 1980s experimentation continued. In 1987, Nicolet Corporation released the world’s first fully digital hearing aid. However, the device wasn’t well received, and Nicolet soon shut down. This setback ignited competition among other manufacturers to develop a better version.

Around this time, AT&T exited the hearing aid market and sold its intellectual property to ReSound Corporation (now GN ReSound).

ReSound’s advanced hybrid digital/analogue device was a major success, prompting other companies to follow suit.

History of Hearing Aids - 21st Century High-Tech

Since the early 2000s, digital hearing aids have become standard, with over 95% adoption by 2005. Technology in these compact devices has rapidly advanced, making them more powerful and user-friendly.

In 2004, Oticon introduced Synchro, the first hearing aid to use artificial intelligence to process sound. This breakthrough transformed how digital hearing aids interpreted sound, paving the way for a wave of innovation across the industry.

In 2006, Starkey pioneered the ELI, the first Bluetooth-enabled hearing aid. It also happened to be the world’s smallest Bluetooth device at the time. Time Magazine recognised its ingenuity, naming it one of the best inventions of the year.

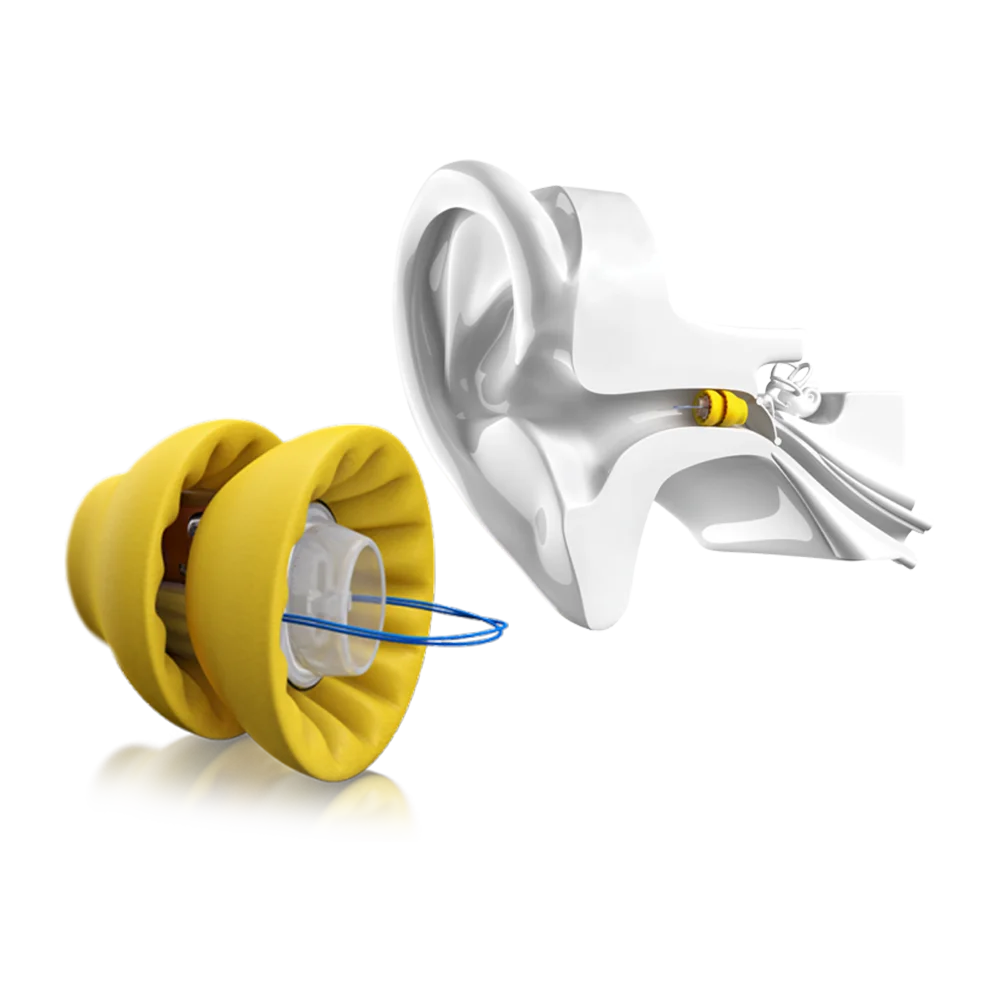

Soon after, Phonak released the Lyric (2008)—the first fully in-the-ear hearing aid designed for continuous wear over several months. In 2010, WIDEX launched the first hearing aid for babies, followed by Siemens’ Aquaris in 2011—the world’s first waterproof hearing aid.

Innovation continued at pace. By 2014, GN ReSound introduced the Linx, the first hearing aid capable of fully streaming audio, while Oticon’s OPN brought internet connectivity to hearing devices.

In 2019, Starkey unveiled the Livio AI range—a sophisticated AI-powered hearing aid with health tracking, app integration, and fall detection. These features proved especially valuable for older users.

A year later, ReSound launched the ONE range, featuring Microphone and Receiver In-Ear (M&RIE) technology for a more natural, immersive sound experience.

Looking Beyond the Horizon

Looking at the evolution of hearing aids, it’s clear that periods of rapid innovation have often been followed by brief lulls. Based on recent breakthroughs, we’re likely still in a phase of fast-paced progress.

That said, some experts argue that today’s hearing aids are nearing peak functionality. With features like Bluetooth streaming, AI sound balancing, on-the-go charging, and integrated microphones and receivers, innovation may slow as the tech reaches maturity.

Then again, the rise of AI could spark yet another revolution. If current trends continue, hearing technology may evolve faster than ever.

Either way, it’s an exciting time for hearing aid users and hearing care professionals alike. And there’s every reason to believe the best is still to come.